The following exercises are related to general properties of the many-electron atoms / ions, especially ground-state and magnetic properties.

They must be solved based on some (usually approximate) quantum-mechanical treatment (Hartree-Fock approximation to Schrödinger's wave equation, and consequent effective-Z approximation...).

The nuclear charge is assumed to be Z qe.

a0 = ℏ²/(me e²)

is the Bohr radius and

EHa = e²/a0 is the Hartree

energy.

Here me is the electron mass and

e² = qe² /(4πε0)

is the electromagnetic characteristic coupling constant.

For many-electron atoms reduced-mass corrections are irrelevant and conceptually meaningless.

This leaves us with 2 problems: (i) determining which are the resulting states (ii) which is their energy ordering.

The way to do it properly is to construct a table of all the states, labeled by their individual ml and ms. For example for two p electrons:

| ml(1) | ms(1) | ml(2) | ms(2) | ML | MS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | -1 | -1/2 | -1 | +1/2 | -2 | 0 |

| 2 | -1 | -1/2 | 0 | -1/2 | -1 | -1 |

| 3 | -1 | -1/2 | 0 | +1/2 | -1 | 0 |

| 4 | -1 | +1/2 | 0 | -1/2 | -1 | 0 |

| 5 | -1 | +1/2 | 0 | +1/2 | -1 | 1 |

| 6 | -1 | -1/2 | +1 | -1/2 | 0 | -1 |

| 7 | -1 | -1/2 | +1 | +1/2 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | -1 | +1/2 | +1 | -1/2 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | -1 | +1/2 | +1 | +1/2 | 0 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | -1/2 | 0 | +1/2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 | -1/2 | 1 | -1/2 | 1 | -1 |

| 12 | 0 | -1/2 | 1 | +1/2 | 1 | 0 |

| 13 | 0 | +1/2 | 1 | -1/2 | 1 | 0 |

| 14 | 0 | +1/2 | 1 | +1/2 | 1 | 1 |

| 15 | 1 | -1/2 | 1 | +1/2 | 2 | 0 |

| ml(1) | ms(1) | ml(2) | ms(2) | ML | MS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1' | -1 | +1/2 | -1 | -1/2 | -2 | 0 |

Next, one starts with the state with maximum value of ML=2 (here, state |15>). One notes that it is orbitally symmetric under exchange of electrons 1 and 2. This state must therefore be a spin singlet (spin-antisymmetric). In addition, this state is the largest-ML component of a L=2 multiplet, made up therefore of 5 components: |L=2,ML=2>, |L=2,ML=1>, |L=2,ML=0>, |L=2,ML=-1> and |L=2,ML=-2>. The first state, as we already said, is state |15> in the table. The next one must have the same space symmetry, thus it must be an orbitally-symmetric (and spin-antisymmetric) combination of states |12> and |13>. Then |L=2,ML=0> must be again an orbitally-symmetric (and spin-antisymmetric) combination of states |7> and |8>, with some admixture of |10>, and so on. These 5 states are indicated by the symmetry label 1D2.

After locating these first 5 states, we remove them from the table (for example by drawing a bar on them), and are left with 10 states. Again we look for the largest-ML state among those left: we see that we have just one ML=1 state, the orbitally-antisymmetric (and spin-symmetric) combination of |12> and |13>.

As it is spin-symmetric it has to be a spin triplet (S=1) state, the MS=0 component of three states, two others of which are: |14> (MS=1) and |11> (MS=-1). These three states form altogether the ML=1 component of a L=1 orbital triplet. The ML=-1 component is clearly formed by: the orbitally-antisymmetric (and spin-symmetric) combination of |3> and |4> (MS=0 component), plus states |5> (MS=1) and |2> (MS=-1). The ML=0 component has a MS=0 component given by a suitable mix of |7> and |8> (no admixture of |10>... why?). The MS=1 and MS=-1 components are clearly given by |9> and |6> respectively. We have in total 3×3=9 states making up a 3PJ=0,1,2 multiplet.

15-5-9 = 1 state is left out of these cancellations: it is the remaining orbitally symmetric and spin antisymmetric combination of |7>, |8>, and |10>, the one orthogonal to the ML=0 component of the 1D2 state. This combination has only one ML=0 and MS=0 component, it is therefore a nondegenerate spin and orbital singlet 1S0 state.

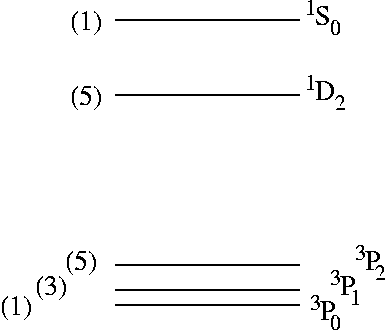

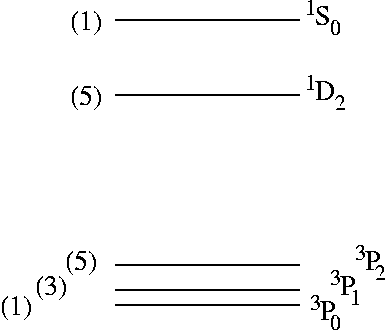

In summary, we have classified the 15 states in the table into:

In summary, the multiplet ordering for increasing energy results as draw in the figure at the right.

A similar procedure can be carried out, with more or less pain and trouble for any shell and any number of electrons.

When electrons belong to different shells, all the multiplet states are found by listing all those for each shell, and making the direct product, with the usual combination rules for angular momentum. For es. a p5d1 configuration yields all multiplets with total L=1,2,3 and total S=0,1 [for a total of 6×10 = 60 = (3+5+7)×(1+3) states].

Like in the single-shell case, the first two of Hund's rules provide useful indications for the ordering of the states. The J-ordering is decided case by case by which of the several spin-orbit couplings prevails.

Note: the ground-state symmetry of all the elements is reported in this colorful periodic table.

The magnetic moment of an orbitally nondegenerate state (L=0) (e.g. an half-filled atomic shell) is purely of spin origin, thus it has a g-factor g=gS=2, irrespective of the number of electron spins cooperating to build up the total spin of the atom/ion. The magnetic moment of a spin-nondegenerate state (S=0) is purely of orbital origin, therefore it has a g-factor g=gL=1, irrespective of the number of electron orbital motions cooperating to build up the total L of the atom/ion. A nondegenerate state of total L=0 and S=0 (e.g. a "closed" atomic shell) has no magnetic moment, thus no first-order coupling to an external magnetic field.

In the generic case one may meet nonzero both L and S. In that case, even in absence of field, the large degeneracy (2 L+1)·(2 S+1) is partly split by the spin-orbit interaction, of the form:

HSO = ξ L·S/ℏ2

[here ξ is the effective spin-orbit coupling introduced above]The eigenstates of the spin-orbit interaction are simultaneous eigenstates of the 4 commuting operators L2, S2, J2, and Jz. The (2 L+1)·(2 S+1) states are split into (L+S-|L-S|+1) multiplets of states, each labeled |L,S,J,MJ>, with MJ (the quantum number associated to Jz).

For example, the 6 spin-orbital states associated to the 2p "level" in the H atom are split by HSO into the two multiplets, labeled |L,S,J,MJ>=|l,s,j,mJ>=|1,1/2,j,mJ>:

|1,1/2,1/2,1/2> and |1,1/2,1/2,-1/2>

|1,1/2,3/2,3/2>, |1,1/2,3/2,1/2>, |1,1/2,3/2,-1/2>, and |1,1/2,3/2,-3/2> ,

separated by 3/2 ξ= 3/2 31.13 µeV= 57.9 µeV.The coupling with the external magnetic field B leads to an additional term in the Hamiltonian:

HB = -µtot·B = -(µL+µS)·B = -µB (gL L/ℏ + gS S/ℏ)·B

Unfortunately, the operator J2 does not commute individually with neither Lz nor Sz. For this reason, as soon as a magnetic field is turned on, the basis of spin-orbit eigenstates is no more a basis of actual eigenstates for the total Hamiltonian of the system H=HSO+HB.It turns out that, for very weak field these states are still fairly good approximations to the real eigenstates (people say that J and MJ are approximate quantum numbers. In the limit of weak field, one can show that the effect of the magnetic field is to split the (2 J+1) degeneracy of each J-multiplet according to:

Heff = -µeff(L,S,J)·B = µB gLandé(L,S,J) (J/ℏ) · B

where the effective magnetic moment of a J-multiplet is given in terms of the dimensionless Landé g-factor gLandé(L,S,J)=[3 J(J+1) +S(S+1) -L(L+1)]/[2 J(J+1)].In other words, in the weak-field limit, the main splitting between the levels is given by the spin-orbit term HSO = ξ L·S/ℏ2 = ξ[J(J+1)-L(L+1)-S(S+1)]/2. Each of the [initially (2 J+1)-degenerate] levels given by this main structure is then split according to ΔE(MJ)= µB gLandé(L,S,J) MJ·Bz, where we have assumed that the z axis is oriented along the direction of the external magnetic field B.

In the opposite limit of strong field, the main structure of the spectrum is given by the HB. The eigenstate are approximately those of the ξ=0 case. They are labeled, for example, by |L,S,ML,MS>. All spin-orbit effects can conveniently be ignored, in the limit of "sufficiently large" field.

Therefore, the magnetic energies are trivially given by Emagn(ML,MS)= µB (gLML+gSMS)·Bz

For an intermediate field, the spectrum has an irregular shape, that interpolates continuously between the two limiting cases.

If the electronic state involves a single electron (as, for example, for the optical-electron states of alkali metal atoms or for core hole states), then a modified 1-electron formula gives an useful approximation:

ξ = EHa (Zeff-SO)4 α2 [n3 l (l+1/2) (l+1)]-1

where the Hartree energy EHa =2 ERy = qe2/(4 πε0 a0), α is the fine-structure constant characteristic of relativistic corrections in atomic physics and l and n are the one-particle quantum numbers of the 1-electron state considered. The above formula is exact (with Zeff-SO=Z) for 1-electron atoms, and may be derived (EXERCISE!) from the relativistically correct expression of the eigenenergies of the 1-electron atom.

The effective Zeff-SO for many-electron atoms is different from the Zeff that gives approximate expressions for the level positions, and usually Zeff<Zeff-SO<Z (EXERCISE: explain the reasons for these inequalities). Both Zeff and Zeff-SO depend on n, and for small n they are close to Z, while in the limit of large n they both converge to the residual core charge (Z-1 for neutral atoms).

The universal constant α2 EHa = 1.44904 meV sets the scale of the spin-orbit interaction. Clearly, the strong Zeff-SO-dependence affects the observed level splitting very strongly. For example, the splitting of the two 2p states of H is 3/2 ξ(n=2)= 3/2 α2 EHa/48 = 0.0453 meV, while for Cs a separation of 44.2 meV between the J=5/2 and J=7/2 states of the lowest 4F excitation is observed, corresponding to a Zeff-SO=14.7 (to be compared to Z=55 for Cs).

For electronic configurations involving several electrons, the spin-orbit operator acts as the sum of the individual spin-orbit couplings for each electron. In LS coupling this can be seen as an effective "total" spin-orbit coupling the total angular momenta L and S. The precise value of the effective spin-orbit parameter multiplying the operator L·S can be deduced case by case. It may even become negative for a more-than-half-filled shell.